It’s wild to think how far No Joy have travelled to reach Bugland. Back in 2010, Jasamine White‑Gluz gave us Ghost Blonde, an album of snarling guitars and buried vocals that nailed the sweet spot between shoegaze haze and grunge punch. By the time Wait to Pleasure arrived in 2013, the fuzz had thickened and the songwriting felt sharper hinting at pop instincts under the noise.

Then came the left turns. More Faithful in 2015 dived even deeper into contrasts: crystalline guitars against bone‑rattling riffs. Motherhood in 2020 turned everything upside down. It swapped distortion walls for restless genre‑hopping, pulling in breakbeats, digital horns and near‑bubblegum hooks. White‑Gluz showed she could bend her sound without breaking it. All of this built the road to Bugland. It’s not a return to the old noise nor a complete departure. Instead, it’s something stranger and more intricate, a record that sits comfortably next to Boards of Canada, Autechre and yes, even the Stooges’ Fun House sax chaos.

Part of that evolution came through collaboration. White‑Gluz paired with Fire‑Toolz (Angel Marcloid), both having moved into wooded, secluded surroundings before recording. Marcloid was pretty clear on how she found the sessions.

“The collaboration really felt limitless. I didn’t have to adhere to a certain vision in a way that made me feel like I couldn’t be Fire-Toolz. I could easily relate to this album because Jasamine and I liked a lot of the same music, and I was able to be creative in ways that were freeing as if I was making my own album. “

They spent days cruising empty rural highways, listening to rough mixes, letting the music sink into new landscapes. That openness filters into every layer of Bugland. At moments it brushes shoegaze, then drifts into digital sprawl, then swerves into something weirder still. It feels personal yet playful, futuristic yet rooted in love for past textures.

Let’s drop the needle and wander through each track and see what secrets Bugland holds.

The album opens with ‘Garbage Dream House’ appearing like a slow‑moving fog. Digital textures ripple underneath guitars that flicker in and out of focus. White‑Gluz’s voice feels almost translucent, floating just above a pulse that never fully locks in. There’s a real sense of patience in all aspects of then production. Nothing’s rushed, everything breathes. It feels like stumbling on an abandoned neon sign flickering in the woods. Those “influence eggs” the band hinted at surface subtly: hints of Cocteau Twins sparkle and the ghost of early trip‑hop lurking in the background beats. The song really picks up intensity in that last section before resolving to digital orchestration and the artifacts that lead us into the title track.

‘Bugland’ steps forward with more muscle. Guitars bend around each other in warped shapes, refusing to settle into clean chords. There’s something almost playful in how White‑Gluz lets melodies fragment then reappear. The low-end rumbles in a way that’s physical without being heavy. Listening closely, you hear little synth details darting in the corners, adding an anxious energy. The tension never fully resolves, it just coils tighter until the track fades out, unresolved but magnetic.

‘Bits’ bursts open as a euphoric slice of shoegaze pop wrapped in a trip hop blanket and flung through the internet at high speed and low resolution. There’s an instant charge — guitars shimmer in pixelated arcs, while stuttering beats rattle underneath. That pop‑leaning energy doesn’t hold for long though. Midway, the track softens into something closer to an eighties ballad, where synth lines glow and White‑Gluz’s vocals slip into a gentler, more reflective register. Just when it feels settled, the heavy guitar textures roar back in, pulling everything out of that dream and dropping us right back into noise and rush. It’s that tug‑of‑war between calm and chaos that makes ‘Bits’ stick, always moving, always catching you off guard making this my album highlight.

A title that feels throwaway at first glance, but ‘Save the Lobsters’ is anything but. It starts almost skeletal, a dry beat, minimal bass before it blooms into subtle synth washes. White‑Gluz’s voice floats like it’s been beamed in from a different song entirely. It’s a reminder of her skill at making contrasts feel seamless: hard edges against soft melodies, synthetic sounds brushing up against organic ones. It’s catchy in its own crooked way, never settling into a proper chorus but still lodging itself in your head.

‘My Crud Princess’ almost drifts into the territory of a traditional pop song (whatever that might mean in Bugland’s universe). There’s a clear verse‑chorus pull and a melody that feels instantly familiar. But it’s what surrounds that core that keeps it from feeling safe. Elongated, stretched‑out guitar notes float across the mix, bending and warping rather than settling into neat chords. The bass feels cavernous and drenched in effects, giving the track a woozy undercurrent that refuses to stay still. It’s recognisable but restless always hinting there’s something stranger lurking under the surface.

‘Bather in the Bloodcells’ leans right into that eighties pop aesthetic at first, with glossy synth textures and a melody that wouldn’t sound out of place on an old cassette single. It doesn’t stay there long though. The track snaps back into futuristic experimentation, twisting familiar shapes into something more unsettling. Goth flourishes haunt the bassline, giving it a brooding undercurrent, while the drums flirt with industrial motifs, all clatter and grit. It turns into a veritable smorgasbord of sounds both nostalgic and forward‑looking all at once, refusing to settle or explain itself.

Up next ‘I hate that I forget what you look like’ maintains that eclectic, fast and loose genre‑hopping style that Bugland wears so well. It’s simultaneously nineties indie, eighties new wave and futuristic space rock. Guitars chime with an almost jangly brightness, synths drift in like radio signals from another planet, and the rhythm section keeps everything grounded without ever feeling rigid. What’s wild is how it holds together, not just as an experiment but as something that feels fully formed. It shouldn’t make sense, yet it does. It doesn’t just sound coherent; it feels deliberate, confident and oddly complete.

The big closer and a proper sprawl of a song comes ‘Jelly Meadow Bright’. Seven minutes where all the record’s ideas come together. Saxophone lines tear across the mix while synth pads swirl around like spa music gone beautifully wrong. Fire‑Toolz’s presence adds glitchy textures and unexpected chord turns. What makes it special is how it never feels stitched together; it flows, shifts and mutates organically. It ends not with a climax but with a gentle release, as if the album exhales and drifts away.

Bugland feels like a record built from contradictions that somehow slot together perfectly. Grit and gloss, nostalgia and future shock, pop instinct and wild experimentation, all sharing the same space without stepping on each other’s toes. What stands out most is how fearless it feels. Jasamine White‑Gluz and Fire‑Toolz never seem to ask whether something fits a genre or a scene. Instead, they lean into curiosity, letting each song wander where it wants That restless spirit makes Bugland a fascinating place to visit. It’s an album that makes you stay alert, to catch the strange details hiding under the surface. You come away with the sense that No Joy’s journey is far from finished. Each release moves further out, peeling back more layers. And if this is where that road has taken them for now, it makes you wonder just how much further they’re willing to go.

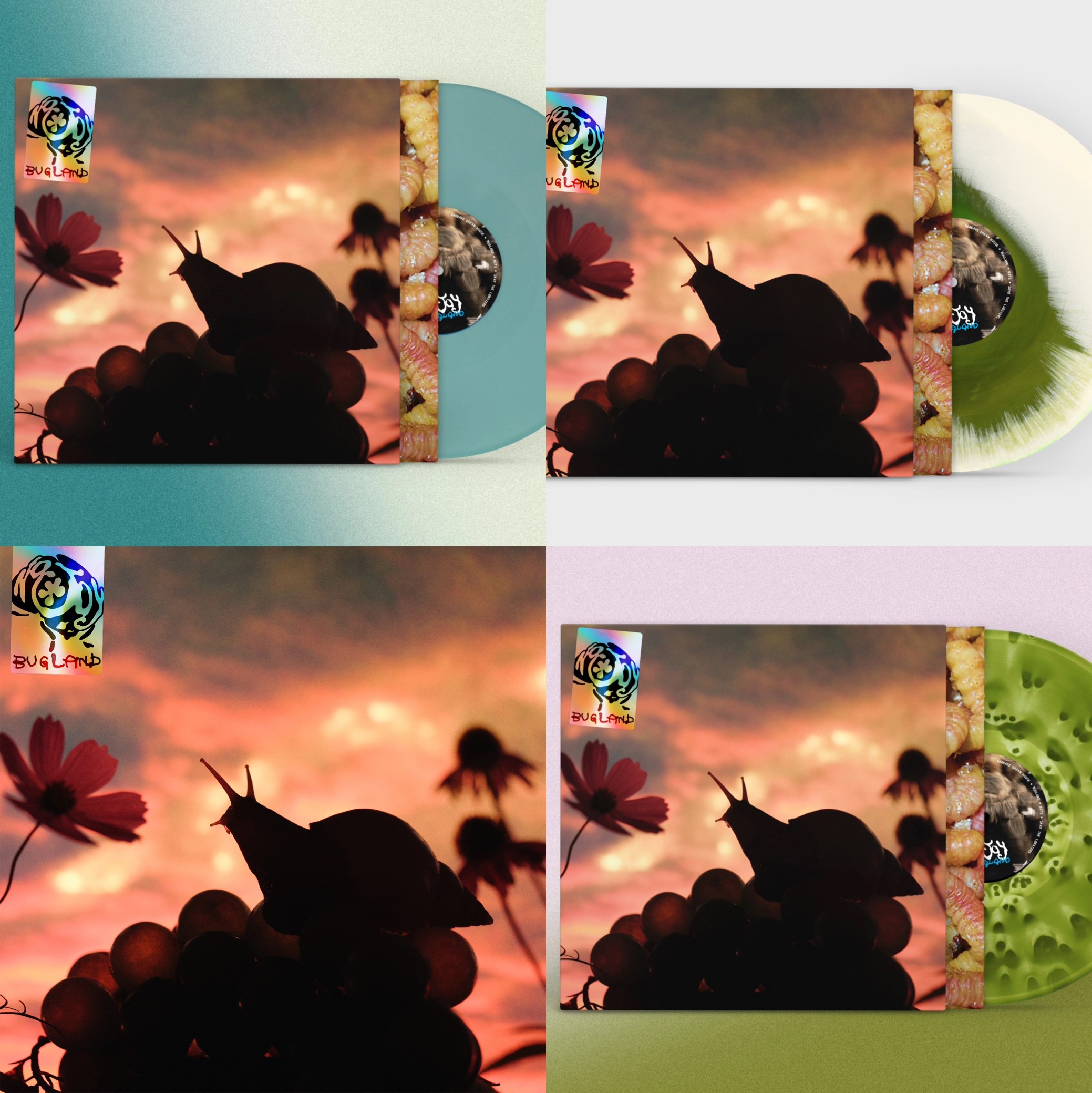

Bugland releases on August 8th 2025 via Sonic Cathedral. Make sure and go check out the album on the No Joy Bandcamp page.

You can follow No Joy on social media here…

Discover more from Static Sounds Club

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.